Bipolar disorder: What is it, types, symptoms, prevalence, causes, diagnosis and treatment

What is bipolar disorder?

Bipolar disorder is a mental health condition that affects mood, characterised by severe shifts in mood that will range from one extreme to the other. The shifts in mood can be low (depressive), high (manic) or a mix of low (depressive) and a variation of high (mania) symptoms such as restlessness and overactivity. These shifts in mood are more intense and last longer than typical mood changes, and they significantly impact a person’s ability to function.

Bipolar disorder can be a lifelong struggle for those who experience it. But with support and treatment, it is possible to manage bipolar disorder and lead a fulfilling life.

Get support for bipolar disorder

Our team is available for a confidential conversation about what you are experiencing and how we can support you. Complete the enquiry form below and our team will be in contact with you.

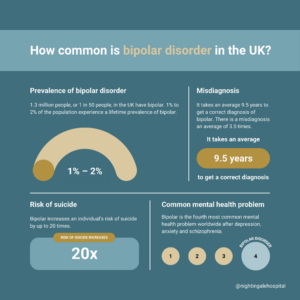

How common is bipolar disorder?

People of all backgrounds and genders are equally likely to experience bipolar disorder.

- 3 million people, or 1 in 50 people, in the UK have bipolar.1

- 1% to 2% of the population experience a lifetime prevalence of bipolar and recent research suggests as many as 5% of us are on the bipolar spectrum.2

- It takes an average 9.5 years to get a correct diagnosis of bipolar and there is a misdiagnosis an average of 3.5 times.2

- Bipolar increases an individual’s risk of suicide by up to 20 times.2

- Bipolar is the fourth most common mental health problem worldwide after depression, anxiety and schizophrenia.3

Symptoms of bipolar disorder

People with bipolar disorder have episodes of depression and mania. Symptoms of bipolar disorder depend on which episode you are experiencing.

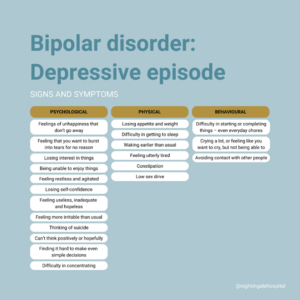

Depression

In clinical depression or bipolar disorder, depression is extreme. It goes on for longer and makes it difficult or impossible to deal with day-to-day life.

Common signs and symptoms of a depressive episode include:

Psychological:

- Feelings of unhappiness that don’t go away

- Feeling that you want to burst into tears for no reason

- Losing interest in things

- Being unable to enjoy things

- Feeling restless and agitated

- Losing self-confidence

- Feeling useless, inadequate and hopeless

- Feeling more irritable than usual

- Thinking of suicide

- Difficulty to think positively or hopefully

- Finding it hard to make even simple decisions

- Difficulty in concentrating

Physical:

- Losing appetite and weight

- Difficulty in getting to sleep

- Waking earlier than usual

- Feeling utterly tired

- Constipation

- Low sex drive

Behavioural:

- Difficulty in starting or completing things – even everyday chores

- Crying a lot, or feeling like you want to cry, but not being able to

- Avoiding contact with other people

Mania

Mania is the presence of an extremely elevated mood where an individual may feel overly energetic or euphoric. It can be so intense that it affects thinking and judgement. People experiencing mania may believe strange things, make bad decisions, and behave in odd, harmful and occasionally dangerous ways.

Like depression, it can make it difficult or impossible to deal with life effectively. A period of mania can affect both relationships and work. When it isn’t so extreme, it is called ‘hypomania’.

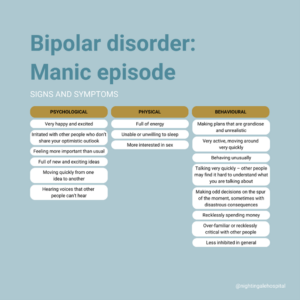

If someone is experiencing mania, they may experience psychological, physical and behavioural symptoms.

Common signs and symptoms of a manic episode include:

Psychological:

- Very happy and excited

- Irritated with other people who don’t share your optimistic outlook

- Feeling more important than usual

- Full of new and exciting ideas

- Moving quickly from one idea to another

- Hearing voices that other people can’t hear

Physical:

- Full of energy

- Unable or unwilling to sleep

- More interested in sex

Behavioural:

- Making plans that are grandiose and unrealistic

- Very active, moving around very quickly

- Behaving unusually

- Talking very quickly – other people may find it hard to understand what you are talking about

- Making odd decisions on the spur of the moment, sometimes with disastrous consequences

- Recklessly spending money

- Over-familiar or recklessly critical with other people

- Less inhibited in general

Someone in the middle of a manic episode for the first time, may not realise that there is anything wrong – although their friends, family or colleagues will. The individual may even feel offended if someone tries to point it out to them. The individual will increasingly lose touch with day-to-day issues – and with other people’s feelings.

Psychotic symptoms of bipolar disorder

If an episode of mania or depression becomes very severe, someone may develop psychotic symptoms.

- In a manic episode: These will tend to be grandiose beliefs about themselves, they may feel they are on an important mission or that they have special powers and abilities.

- In a depressive episode: People might feel they are uniquely guilty, they are worse than anybody else, or even that they don’t exist.

As well as these unusual beliefs, sufferers might experience hallucinations – when they hear, smell, feel or see something, but there isn’t anything (or anybody) there to account for it.

Between episodes

It used to be thought that if someone had bipolar disorder, they would return to normal in between mood shifts. However, research has now shown that this is not the reality for many people living with bipolar disorder. They may continue to experience mild depressive symptoms and problems in thinking, even when they ‘seem’ to be better.

Types of bipolar disorder

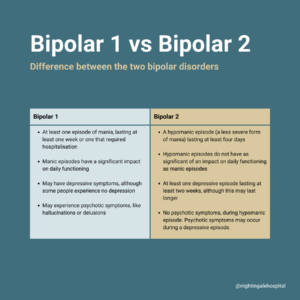

There are officially four types of bipolar disorders, namely: Bipolar 1 Disorder, Bipolar 2 Disorder, Cyclothymic Disorder (Cyclothymia) and Other specified or unspecified Bipolar and related disorders. The two most common diagnoses are bipolar 1 and bipolar 2.

Bipolar 1

In order to receive a diagnosis of bipolar 1, you need to have experienced at least one episode of mania, lasting at least one week or one that required hospitalisation

The type of mania characterised by a diagnosis of bipolar 1 is intense and severe, having a significant impact on daily functioning. This type of mania may cause symptoms such as:

- Abnormally high levels of energy

- Feelings of euphoria

- Feeling rested after only a few hours of sleep

- Thinking you’re invincible, engaging in impulsive decision making or risk-taking behaviours

- Talking so fast that others are not able to interrupt

- Racing thoughts, having lots of thoughts on different topics at the same time

- Becoming obsessed or completely absorbed in an activity

- Pacing around your home or fidgeting when sitting

- May experience psychotic symptoms, like hallucinations or delusions

Depressive episodes typically follow manic episodes and can last at least two weeks, but there presence is not necessary for a diagnosis of Bipolar 1 disorder.

Bipolar 2

In order to receive a diagnosis of bipolar 2, you need to have experienced:

- A hypomanic episode (a less severe form of mania) lasting at least four days

- At least one depressive episode lasting at least two weeks, although this may last longer

- No psychotic symptoms present during hypomanic episode

Hypomanic episodes have a lot of the same features of manic episodes but are not as severe and do not have as much of an impact on daily functioning. The dominant concern in bipolar 2 is generally the depressive episodes, which tend to be long lasting and severe.

Get support for bipolar disorder

Our team is available for a confidential conversation about what you are experiencing and how we can support you. Complete the enquiry form below and our team will be in contact with you.

What causes bipolar disorder?

Many mental health conditions have multifaceted causes which are made up of several interrelated components. There is no one cause of bipolar disorder. Rather, research suggests that a combination and interplay of factors in your biology, psychology and social environment contribute to the development of bipolar disorder.

Biological factors

These refer to the genetic, neurochemical, and physiological components that contribute to bipolar disorder.

- Genetics: Research has shown there is a strong genetic component to bipolar disorder and that people with a family history of the disorder are at a significantly higher risk. Tracing the familial link of bipolar disorder is not as simple as finding a single gene linked to bipolar. Rather, family links of bipolar are much more complex and also include social factors of early development. However, even if you have a family member with bipolar, it does not mean that you will develop it.

- Chemical imbalances in the brain: There is evidence that symptoms of bipolar can be linked to imbalances in neurotransmitters, the ‘messenger chemicals’ responsible for controlling the brain’s functions. There is evidence that when these levels become too low or too high, you may experience mania, hypomania or depression. Medication used in the treatment of bipolar works by altering these neurotransmitters that help regulate mood and behaviour.

Psychological factors

These focus on cognitive, emotional, and personality-related influences that may predispose someone to bipolar disorder.

- Cognitive patterns: Negative thinking styles, such as excessive self-criticism or perfectionism, can exacerbate symptoms of bipolar disorder. Cognitive distortions can worsen depressive episodes, while grandiosity or unrealistic thinking may contribute to manic phases.

- Trauma or stress: Early life trauma, such as childhood abuse, neglect, or significant stress, is often linked to the development of bipolar disorder. Traumatic experiences may alter the brain’s stress response systems, increasing vulnerability to mood dysregulation later in life.

Social factors

These encompass environmental, cultural, and interpersonal influences that contribute to the onset and course of bipolar disorder.

- Family and social environment: Family dynamics, parenting styles, and the quality of interpersonal relationships can affect the development and management of bipolar disorder. Dysfunctional family relationships or a lack of social support can exacerbate symptoms. Conversely, a stable, supportive environment can help reduce the frequency and intensity of mood episodes.

- Stressful life events: External stressors, such as financial difficulties, relationship problems, or significant life changes (e.g., job loss, divorce), can act as triggers for mood episodes. Stress is thought to activate or worsen underlying biological vulnerabilities.

- Medication, drugs and alcohol: There are some medications which can cause hypomania or mania as a side effect, including some antidepressents. These side effects can happen while you are taking the medication or as a symptom of withdrawal when you stop taking them. Your psychiatrist will discuss any concerns you have about medication side effects and their link to any symptoms of bipolar. Alcohol and recreational drugs can also cause symptoms of mania, hypomania and depression.

How is bipolar disorder diagnosed?

Bipolar disorder carries many of the same symptoms of other mental health disorders, including depression, borderline personality disorder (BPD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and schizophrenia. An assessment with a psychiatrist is a crucial step is getting a correct diagnosis.

A psychiatrist may be able provide a diagnosis during an assessment but since bipolar disorder involves changes in your mood and behaviour, your psychiatrist may want to observe your symptoms over time before providing a diagnosis.

To help in these discussions with your psychiatrist, they may ask you about:

- What symptoms you have experienced

- What types of episodes you have experienced, including length, frequency and severity

- Any patterns or triggers related to your mood

- The impact your symptoms have on your daily functioning

- Family history of mental health

- Your lifestyle, including questions about your physical health

Treatment for bipolar disorder

Bipolar is a lifelong condition, but it can be managed with effective treatment. There are generally two types of treatment options for bipolar disorder: talking therapies and medication.

- Talking therapies: Your psychiatrist may recommend one of several talking therapies to help manage your bipolar. These could include cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT) and group psychoeducation as part of an inpatient or day patient programme. The aim of talking therapy is to empower you with various techniques to manage your bipolar that you can put into practice in your everyday life.

- Medication: Medication can be used to stabilise your mood and behaviours, and reduce the chances of relapse.

In extreme circumstances, and if you have experienced long and severe periods of depression or mania and other treatment have not worked, your psychiatrist may consider ECT as a treatment option.

However, your treatment plan should be individualised, taking into account all other aspects of your mental health. That’s what Nightingale Hospital provides – tailor-made and flexible treatment options based on best clinical evidence and your individual circumstances.

The first step is to be matched with a psychiatrist who will provide an assessment for you. This assessment is to understand your symptoms, provide any diagnoses if relevant and put together a treatment plan specific to you, including clearly defined goals that you can work towards. Your treatment plan may include a period of inpatient, day therapy or outpatient treatment but this will all depend on your individual circumstances and symptoms.